With its tongue-in-cheek title, this unique feminist documentary opens with a theatrical sequence. A couple dances on a stage to then go their separate ways. The camera focuses on the man who, having finished his cigarette, stands on the woman’s shoulders. As the camera moves away, her figure comes into view. Not only does the woman support the weight of the man, but she also holds two children in her arms. The film’s title appears around her body.

After a cut to one of the main streets in Warsaw, we catch a glimpse of a policewoman directing the traffic. The male narrator says: ‘As a man, I can’t be neutral seeing the title and the biased message of this film. We just want to see women as they are every day’.

When the policewoman freezes, the next cut reveals a woman with a camera on a lift over a construction site. Ending in another freeze frame, the shot is replaced by a series of images of women working in male-dominated jobs. We see female pilots, sailors, astronauts and politicians. The male narrator credits men for allowing women to work in such professions.

His exaggerated patriarchal tone is soon countered by a female voice, who sarcastically confirms his words, saying ‘You allowed us to embody the highest ideals of humanity: wisdom, justice, victory, and, of course, love. And then you forgot about it all and sent us to the kitchen.’ Pictures of Athena, Nike, Themis, and Venus accompany these words.

The next cut takes us to a wedding where instead of a ring the groom puts handcuffs on the bride’s wrists. The voice-over now imitates Biblical verses: ‘And the man took her for a wife so that she was faithful and obedient. And then he made her clean, wash, cook and do all the things that he found unpleasant to do.’

Following a little boy who describes his mother doing all the housework, when his father says he’s busy, the male narrator returns: ‘I would have a lot to say, but unfortunately the women who made this film, won’t let me say anymore’.

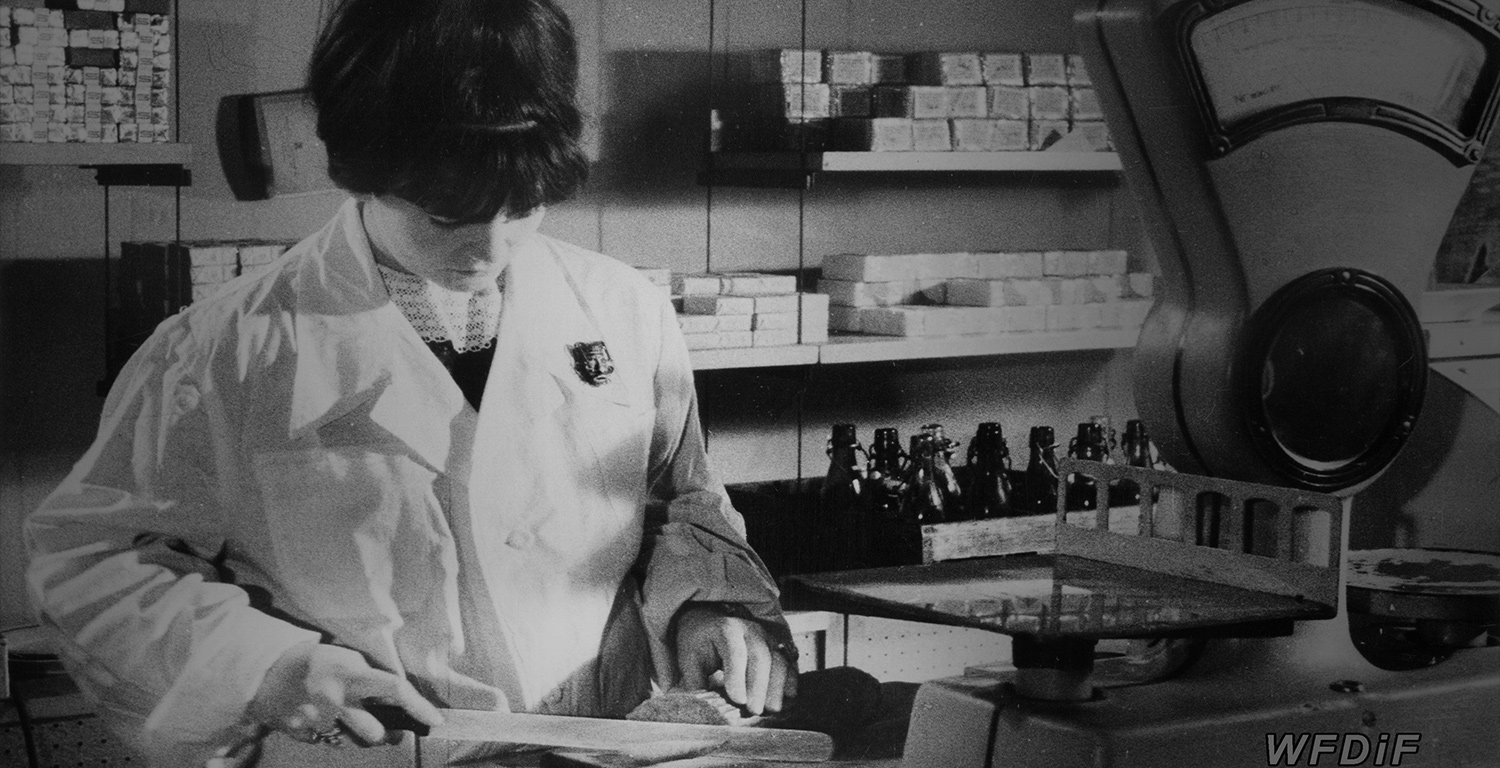

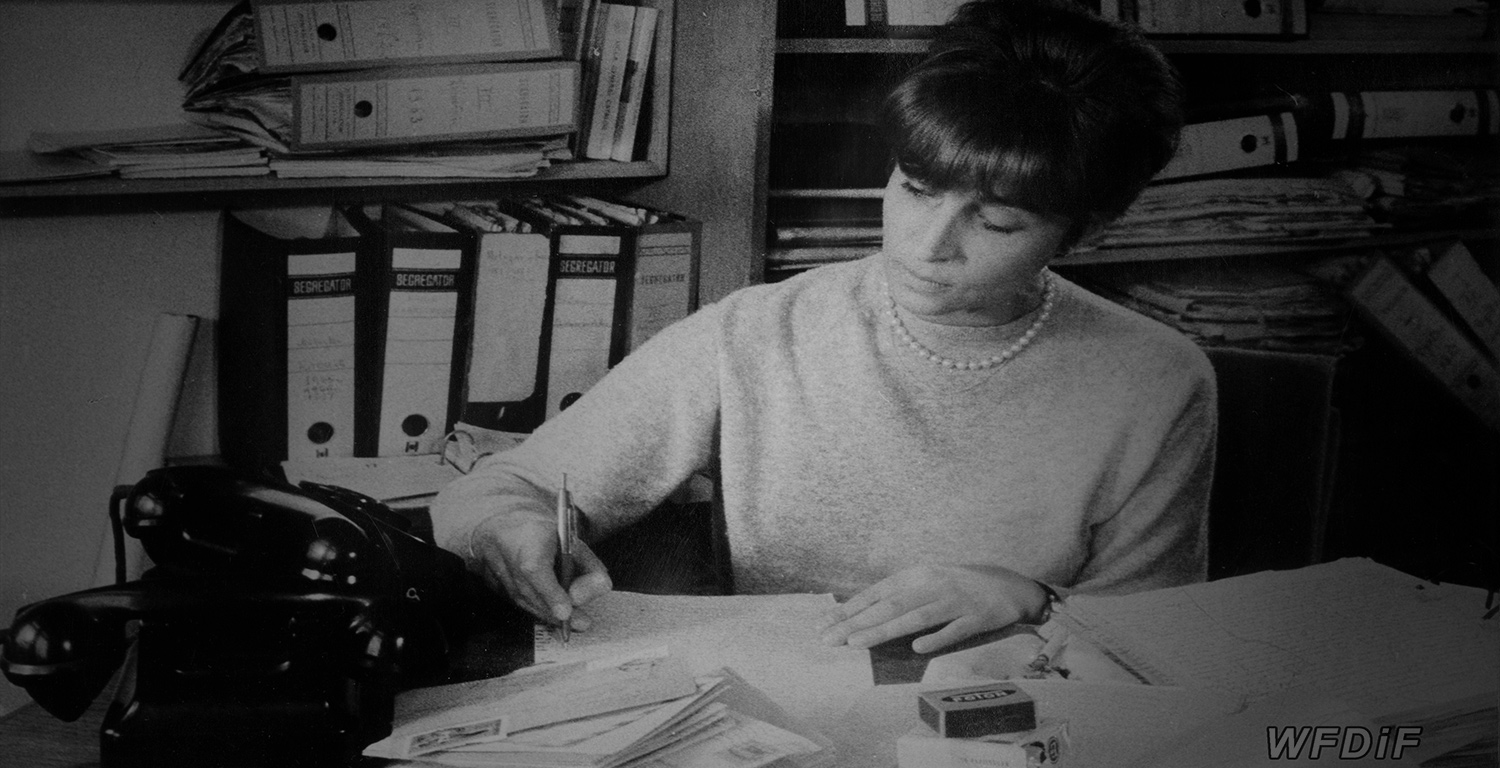

From this point on, the style of the documentary changes. The light-hearted argumentative tone gives way to more down to earth evidence. We watch several women at their workplaces, as they are interviewed by the film crew. They take turns commenting on their relationships with men.

Their opening remarks offer some rather light evidence of unequal labour division between the two genders. The women say that they cook for their husbands who don’t like kitchen work. Before they leave their houses in the morning, they prepare breakfasts for the men. Some men sleep after work, go out or watch television when women attend to their children.

But the unbalanced power relations also have more severe consequences for some of these women’s lives. Their husbands stop them from going to school, leave them with no financial support for their children or tell them that they need younger, more attractive partners. To complete this picture, in the remaining part of the film, letters of desperate women who experience domestic violence are read off the screen.

The closing re-enacted sequence shows a woman carrying shopping bags home and we see her male partner lying in front of the TV with his feet up. Then her hands are busy with kitchen work, his are holding a newspaper. The concluding shot of the film is a wedding photo hanging on the wall. The frame freezes for a few seconds before the final credits inform us that authentic words from interviews have been re-enacted by actors to protect the identity of some female interviewees.

With cinematography by Elżbieta Zawistowska (born 1935), Amiradżibi’s sharp, unconventional outlook at the unequal social treatment of women in the 1960s Poland is probably the only film from that time that openly opposed the patriarchal oppression of women in everyday social circumstances.

RETURN TO Helena Amiradżibi The Weak Woman

RETURN TO Helena Amiradżibi The Weak Woman Read More

Read More View images

View images More films

More films