During the rainy season in November 1970, Ewa Kruk went to Bieszczady—the scarcely populated mountain region in the Southeast of Poland—to meet people who’d decided to take a whack at moving from cities to the countryside. Driven by the hope of returning to simple, natural lifestyle, they’d moved away from civilisation to find liberation from the anxieties of urban living.

As the film shows, their visions of finding a traditional village utopia become hampered not only by the expected shortages of modern comforts but also by the weather. When we first meet them, the cloudy skies over their new homes serve as a metaphor for their mental states. In the midst of daily drizzles, boredom and bleakness replace the initial enthusiasm and some can no longer stand by their choice to venture into the wild.

At the beginning of the film, the camera follows a tractor with a trailer. Families with children, dogs and a few household items travel along a countryside road. They’ve come to resettle villages deserted by locals, who moved away in the opposite direction, to the cities that lured them with easier living conditions.

We meet an anonymous woman standing in front of her house. Off screen, we hear her voice saying: ‘Each creature needs to find its burrow’. A few minutes later, she confirms that the settlers have arrived in Bieszczady ‘to find satisfaction in working for themselves’. Dreams of owning land and being in charge of their destiny led several families, now living in local villages, to resist modern lifestyles in Communist cities and reclaim their freedom in the idyllic countryside environment.

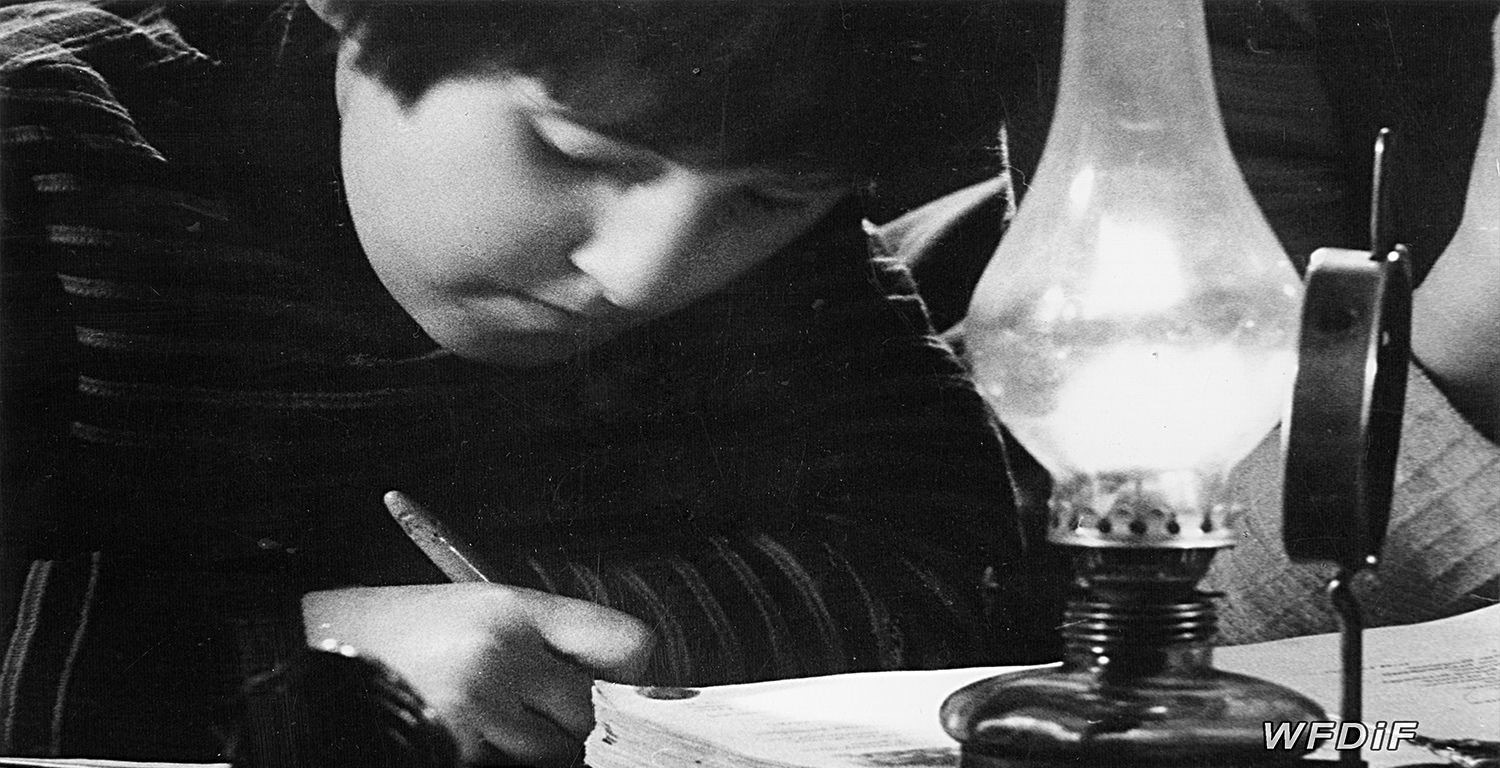

Kruk observes the difficulties the settlers encounter in neglected villages with no electricity, heating or running water. Going back to basics, they build their houses or refurbish old peasants’ huts, cut wood for their stoves and fireplaces, grow their food and raise animals. Their children study using kerosene lamps. Some appear to accept the hardships while others are disappointed with the adversity of nature when in mid-November, the dark and damp houses in the forest look nothing but depressing.

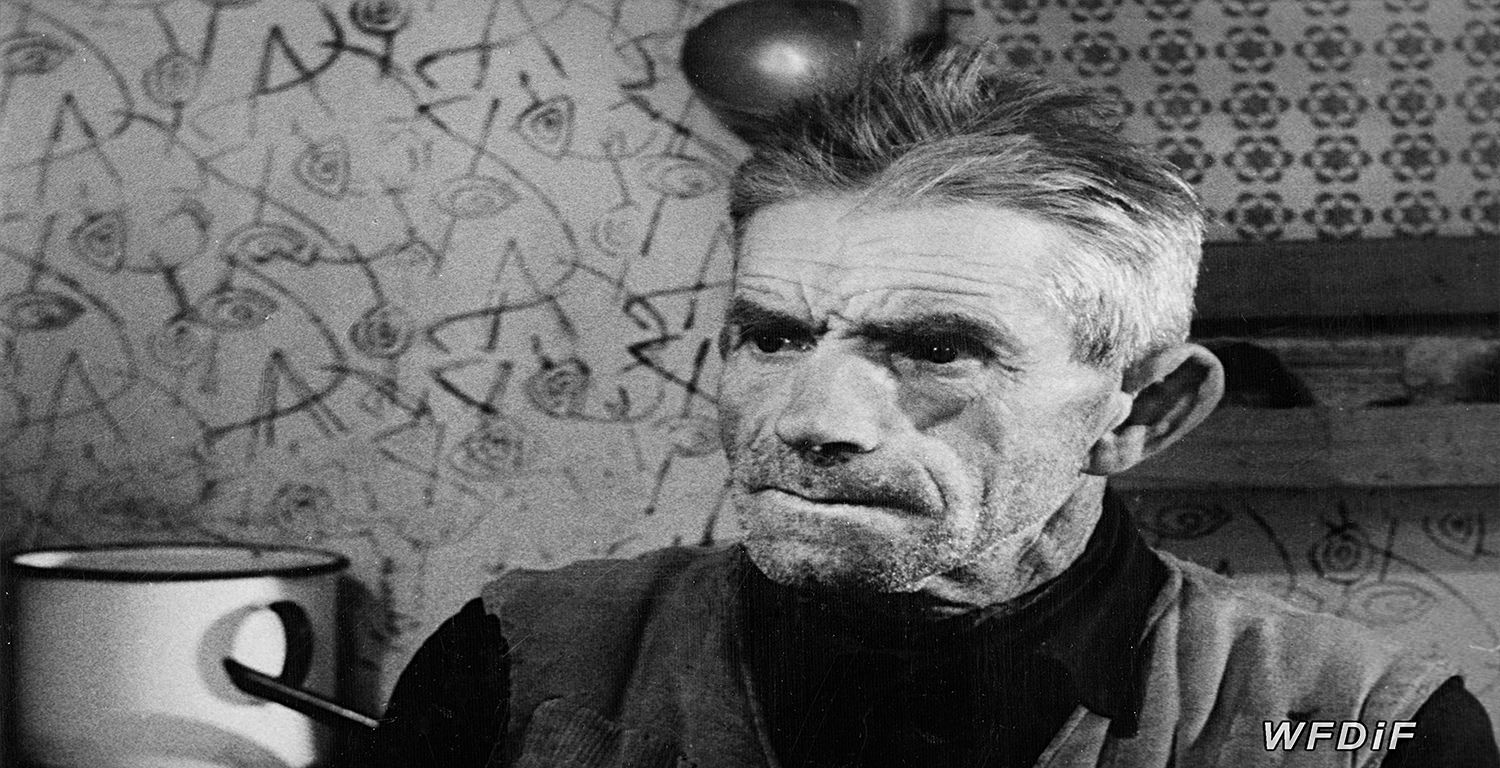

Seeing the settlers flooding their primitive villages, the remaining few natives seem amazed at such an unusual desire to live the organic life. A mature man says to the camera: ‘I would run away from here’. A few older women recall previous settlers who couldn’t cope with the workload or the harsh winters.

Nevertheless, the film closes on a positive note. Having discussed that not even their closest friends and families could understand their migration to the wild, the settlers appear motivated to pursue their ambitions to find a utopian, stress-free paradise. Although under the November skies, these villages in Bieszczady are more reminiscent of hell than heaven, some off-screen voices still resonate with optimism: ‘We have to handle this’.

In the final edit, settler women tidy their plain kitchens and men sow winter cover crops, while their children read books in half-dark rooms. The new minimal and austere farms rise in Bieszczady to house the idealists who in opposition to modern life, chose individual freedom over the Communist collective.

When green lifestyles replaced the comforts of the industrial cities of the 1970s, moves to remote countryside locations manifested as subtle acts of resistance to the social and political systems in the country.

RETURN TO Ewa Kruk The Settlers

RETURN TO Ewa Kruk The Settlers Read More

Read More View images

View images More films

More films